Why the FTSE 100 is finally finding some friends

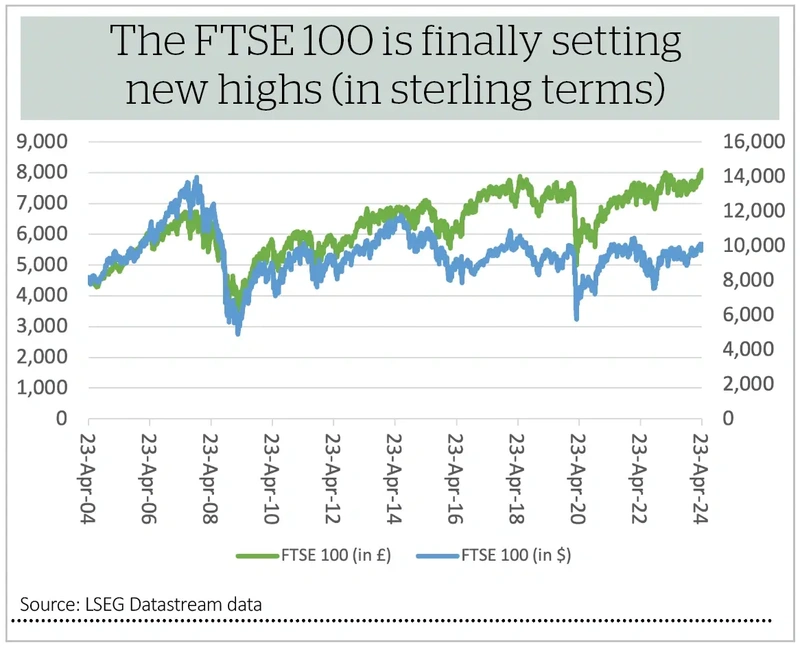

The FTSE 100 is not the best-performing major stock index in the world this year – that honour lies with Japan’s Nikkei 225, which is up by 12% in local currency terms – but the UK’s premier benchmark is (finally) setting new all-time highs, at least when measured in sterling. The picture does not look quite so rosy in US dollars and while this can be used as a pretext to cavil it can also be a further explanation of why the index is gaining fresh traction – it may still look cheap, especially to overseas buyers.

This valuation argument rests on three arguments:

- The pound is yet to recover all of the ground lost in the wake of 2016’s Brexit vote.

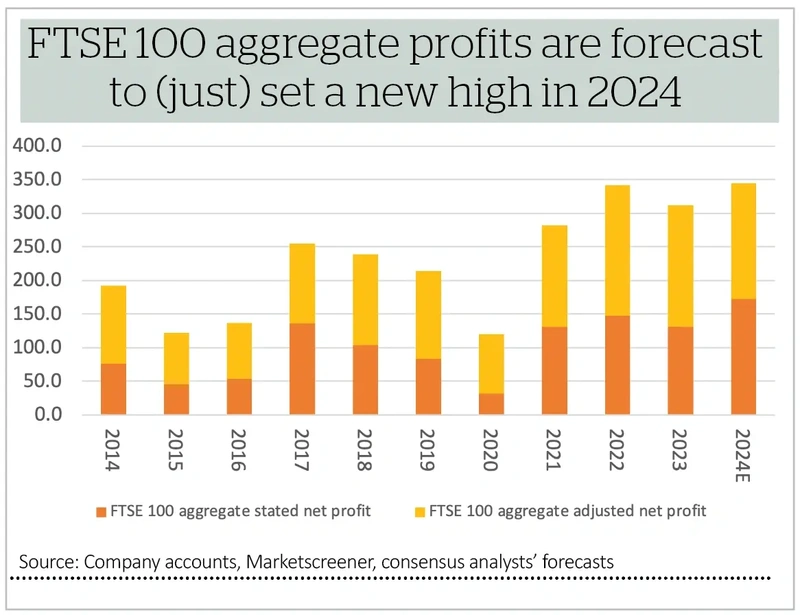

- The FTSE 100 began this year at 7,733, no higher than it had been in spring 2018, even though aggregate profits for 2024 are expected to come in one quarter higher than they did six years ago.

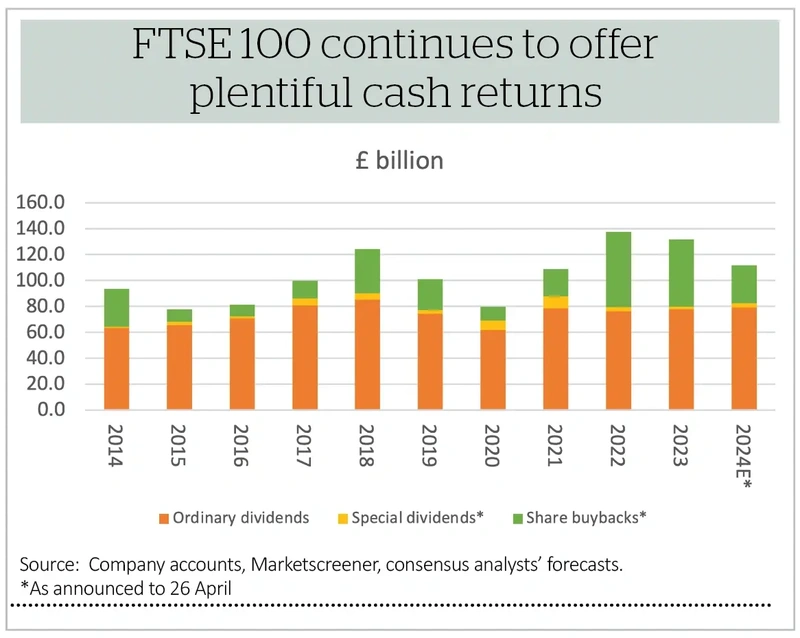

- Aggregate ordinary dividend estimates suggest the total payment in 2024 could come in at £79.1 billion. That is slightly below 2018’s all-time high, but the forecast yield is still 3.7%. Buybacks are on track to at least match last year’s total of £52 billion, another 2.5% of the FTSE 100’s market cap, and takeovers are running at a rate of 1-2% of the UK market cap, as well. Add dividends, buybacks and takeovers together and the cash yield on the UK market is between 7% and 8%, a figure that easily beats inflation, returns on cash and the yields available on gilts.

This matters because valuation is the ultimate arbiter of investment return: paying as low a price as possible both protects the downside, should anything unexpected go wrong, and maximises upside potential, if the investment thesis plays out as expected. Valuations tend to be at their lowest when pessimism is most pervasive, and there is no lack of pessimism regarding the UK’s economic, political and financial prospects right now.

The latest run of takeover bids for UK-listed firms suggests someone feels this presents an opportunity and perhaps they have in mind the maxim offered by the American investor Shelby M.C. Davis, founder of some highly successful value-oriented equity funds: ‘You make most of your money in a bear market. You just do not realise it at the time.’

Possible risks

The FTSE 100 is not in a bear market, as the index is setting new peaks, but you would never guess it, judging by the handwringing about the number of firms defecting to other exchanges, the paucity of new listings and cries for political and regulatory intervention to ‘do’ something. There may be some valid things to do, such as scrap stamp duty and simplify the ISA product offering, for example, but ultimately the best cure for low prices is low prices, because they boost demand (either takeovers or investor buying, in this case) and staunch supply at the same time. High prices, by contrast, choke off buying and encourage supply (as the torrent of dross that listed on the bubbly US exchanges in 2021-22 would attest).

There are still clear risks to the UK equity story, and it is possible that the FTSE 100 is cheap because it deserves to be. There is a general election coming up and a change of government is possible; the nation is heavily indebted; and the Bank of England looks a bit trapped between a low-growth rock and a sticky-inflation hard place, with the result that the cosy consensus narrative of cooling inflation and interest rate cuts is not playing out as hoped.

Those investors who wish to avoid stock-specific risk and access the FTSE 100 via funds, either actively or passively managed, although need to understand the sector exposures they are embracing. Financials, oil & gas, miners and consumer staples such as tobacco dominate the index’s earnings and dividend profiles. Some investors might not approve on ethical, social and governance (ESG grounds). Others may recoil from what they see as low-growth or ex-growth duds.

Possible rewards

Such arguments feed the notion that the UK is cheap because it deserves to be cheap. That narrative has prevailed for what feels like forever, or at least during the era of low growth, low inflation and low interest rates that has done much to push investors toward long-duration assets such as government bonds or secular growth equity sectors such as technology and biotechnology.

But what if that environment is about to change? Perhaps the bill for the ‘free’ money pumped into the economy by zero-interest rate policies, quantitative easing and fiscal stimulus (during Covid) is now having to be paid, in the form of a weak currency or higher inflation or higher rates or higher taxes (or a combination thereof).

If we are indeed entering a different era of higher inflation, higher nominal growth and higher interest rates, history suggests this favours hard assets (commodities) over paper ones (bonds and cash), and short-duration assets (such as cyclical and financial equity sectors) over long-duration ones. That is a lot of ‘ifs,’ ‘buts’ and ‘maybes,’ yet the UK equity market may now offer the ‘right’ sector mix, rather than the ‘wrong’ one, for the first time in a good while.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Feature

Great Ideas

News

- Barclays breaks to 52-week high despite lower earnings

- Shoe Zone shares slump on fears over trading and higher costs

- Stagflation fears rise on resilient US economy and sticky core inflation

- Alphabet joins Meta in shareholder dividend commitment

- What is happening at Smithson after continuation vote dissent?

magazine

magazine